Cover Image: Dan Towsley

From the Editor’s Bench

It is no coincidence that we are sending Issue 003 on opening day of Prairie Chicken season. I suspect a large majority of hunters have not had the opportunity to hunt these magnificent birds. Their numbers and territory are on the decline. Their strongholds are adjacent to places more accessible, with healthier populations of more popular game birds to pursue. Despite all of this, after having read our feature story by Josh Tatman (editor of The Grit Magazine), with stunning photography by Dan Towsley, I’ve added a prairie chicken hunt to my bucket list.

While this feature is a bit longer than most of our Dispatch essays, I urge you to set aside the time to read it in its entirety. It embodies everything we love here at Strung. Storytelling that grabs your senses and draws you into the experience. An emphasis on ethical and responsible harvests. Family, community, and tradition. And an important reminder that as hunters and anglers, we are the tip of the spear in conserving the very species we pursue. As our access to public lands is actively being threatened, getting involved is more important now than ever.

We’ve opted to go with a photo-centric fly fishing feature this month for word relief, and to give a bit of love to warm-water species that are flat out fun to catch on a fly.

Tight lines and Straight Shots,

Sammy

P.S. I’d like to take this time to thank you for reading the Dispatch. Feel free to respond to this newsletter (responses come directly to me) and let me know what you like, what you don’t, and topics you’d like to see going forward. Finally - if this email landed in your promotions or updates folder, drag it to your priority folder to make sure you see future issues. Enjoy!

Refer Friends, Earn Free Stuff

Every referral makes a difference — by inviting friends to join Strung Dispatch, you’re helping us grow this community, keep the newsletter free, and share more stories from the field and water. And you earn great schwag for doing it.

3 Referrals = Sticker Pack (4 stickers)

10 Referrals = Strung Trucker Hat

Rewards are available to U.S. residents only and include free domestic shipping. Referrals must be new, valid subscribers to Strung Dispatch. Duplicate emails, self-referrals, bots, or invalid sign-ups will not count toward totals.

Feature

The Chicken Hunt

Story by Josh Tatman, Photos by Dan Towsley

The truck’s headlights split a curtain of black, illuminating only a hundred yards of gravel road. I shake my head, trying to stay awake. An hour ago was too early for breakfast pizza. Instead, Casey's gas station yielded a power bar and a thin cup of coffee. Neither are sparking my mind to attention.

A blood-red splinter of light glimmers on the eastern horizon. Ahead, there are signs of life. Where the county road turns to rutted dirt, a congregation is gathering. Pickups and SUVs line the grassy ditch. More headlights approach in the rear view mirror as we pull off the shoulder.

We climb out and fumble through gear, thankful that we were wise enough to organize shotguns and boxes of shells the night before. We walk over to join the dark figures that stand in knots, sipping coffee between bumpers. Groggy greetings are exchanged by the group clad in duck camo.

A white Chevy pulls up and the window opens. I shake hands with Jeremy Jackson, our invitation to this dawn assembly. It’s my first time here, but Jeremy has been attending this gathering since he was a little boy. Once a year, every year, the Jackson family holds a unique hunt on the plains of Kansas.

It’s opening weekend for pheasants, but we have no interest in longtails. The weather is just getting cold enough for ducks, but our decoys and indignant dogs stay in the truck as the hunters disperse into a cut hay field. The stubble seems void of any cover that would justify our attention.

Dan Towsley and I drove across most of the Great Plains to get here. Jeremy and Dan did keg stands together back in their Kansas State days, just one of the long threads that connect people across vast landscapes. Dan came here once back in college and has told me stories. Today, I’ll see it for myself.

I’m accustomed to the topographically destitute prairie, but the fact that we are on the edge of the Flint Hills isn’t obvious. Even the heart of the hills to the east would be considered gentle back home in Wyoming.

A moody sunrise dispels the grey light across a plain as we stop at a nondescript fenceline. “We’ll spread out here,” said Jeremy. “Put about fifty yards between you and the next guy. Keep your eyes open.”

Jeremy is a quiet man, the kind that leads you to instinctively hang on his words when he does speak. Nevertheless, his advice is immediately squandered. We haven’t even loaded our guns yet when a black shape whips by on the wind. “Chicken!” someone calls, but the apparition is already gone.

Jeremy is a third generation prairie chicken hunter. His grandfather, Bill Jackson, started an annual pass-shoot chicken hunt over fifty years ago. Now, Jeremy’s dad Billy hosts the event. “It’s something that I wanted to do my part to continue,” Billy said. “It is a good opportunity to introduce folks to chicken hunting. It is also great to get everyone together, including family and friends that you might only see once a year.”

Prairie chickens are to Kansas what ruffed grouse are to Michigan, or what sage grouse are to Wyoming. Billy Jackson thinks that in general, locals are very fond of the birds. “I am fortunate to grow up where we have a unique opportunity here in the Flint Hills. Numbers have declined, but around here people value them as a special bird that has been around since the old days.”

In the Flint Hills, once renowned for prairie chicken hunting, only a few hunters still bother. Jeff Prendergast, Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks, and Tourism (KDWP) Upland Gamebird Program Coordinator, explains the history. “Hunting participation has changed through time but has never been as popular as pheasants or quail. In the modern times prairie chicken hunter numbers have declined and are low relative to other hunter groups.”

The nearby hamlet of Cassoday was once billed as the “Prairie Chicken Capital of the World.” Aging residents tired of being reminded of the way things once were, and took the sign down.

Further northwest, core areas in the Smoky Hills are also experiencing a slow decline. Much of western Kansas is closed to prairie chicken hunting altogether to protect the now federally listed lesser prairie chickens.

Pass shooting chickens may seem a surprising mode of procurement, but these events are a cornerstone of Kansas hunting tradition. Jeff says, “In the 1970s through the 1980s, pass shooting was very popular. This was mostly an opening weekend tradition, but it began declining as changes to grazing practices resulted in fewer chickens and opportunities.”

In areas with good bird numbers, Billy Jackson told me, “It wasn’t uncommon to see three or four hundred chickens flying between feed fields.” Instead of chasing birds around the prairie with dogs, hunters chose to coordinate their efforts in the best spots.

Stationary hunting always leaves me colder than I expect. My dryland bones aren’t accustomed to the moist air, and a stiff south wind buffets us as we man our posts along the fenceline. Far to the north, across the field, we hear a few shots. Cell phones come out as hunters call across hay stubble to get the scoop. Just a few birds, one down.

The morning wanes on, but along our section of fenceline, we’ve only seen a few birds briefly perch on distant power lines. Our guns rest idly on the barbed wire. Pass shooting chickens is a game of chance. There is some skill involved – you need to pick a decent spot and be ready to connect on long shots. It’s clear that luck – or the lack thereof – will prevail over our preparations. We merely wait to see what the skies bring us.

As the sun climbs higher, it becomes apparent that luck is fading. The stiff south wind is keeping any roving birds at bay, with only a few skirting the northern edge of the property. We throw in the towel and head to lunch.

Our route takes us through a checkerboard of fields and pastures. Chickens have a hard go of it in such dissected habitat. Even the native prairie we pass is infested with broomweed, a sure sign of overgrazing. Jeff Prendergrast says the interspersed cropland can be good for winter forage, but, “A little goes a long way. Once grassland makes up less than 60% of the larger landscape, populations are unsustainable. Prairie chickens are a landscape level species- they need large areas of predominantly grassland.”

The wind is really roaring by the time we pull into a farmstead next to a brushy quail bottom. The menfolk and kids are all out front in the lawn, taking turns shooting clay pigeons. I try a few shots with Billy’s 28 gauge, but then head inside where the conversation is quieter.

Phyllis Jackson, Jeremy’s grandmother, worked for many years as a school cook. She is entirely unflustered by the army of hungry bird hunters who await, calmly delegating tasks and chatting away. A huge vat of bone-warming chili awaits, along with all the Midwest trappings: cheddar, Fritos, and cinnamon rolls.

Jeremy’s great uncles Pete Peterson and Larry Jackson pull up honorary chairs at the kitchen table. These two have been hunting prairie chickens since before I was born. They regale us with tales of ridiculous bird numbers in the good old days while Phyllis cuts her pies- she bakes hundreds a year for local functions. I tell myself that I am on vacation to justify a slice of coconut cream and another of peach. I savor them without regret.

Dan and I break off from the group for the afternoon and explore a few quail covers. Luck is with us now, and we flush a nice covey along a grove. We need to get back to the chicken field by late afternoon, but we try one more quail cover before we drive back.

We reach the chicken field around 3:30 and quickly transition from upland orange to camo, then hike out to the far fenceline to meet Jeremy. Halfway there, a flurry of shots erupt. The birds are already flying in. Cussing that last wasted quail walk, we hasten our pace, but there’s no way we can make up the five minutes that would have put us in the right place at the right time.

When we arrive panting, Jeremy is holding a nice hen prairie chicken. His friend’s son Mads examines the limp body in the playful curiosity that kids have for dead things. I’m optimistic that we haven’t missed all of the action, so I load my shotgun. Dan and I try to decide between standing with Jeremy and moving down the property boundary to a shallow swale that cuts through the field.

Naked without the advantage of a dog, it is simply a roll of the dice. Most upland hunting is a game of poker. We try to guess where the birds will be and what they will do. We pick the best cover for our dog to push, and do what we can to tilt luck in our favor. But out here, there’s simply no way to know how many chickens will fly, what exact route they will take, or if they will come at all.

We are running out of daylight when I catch a flutter out of the corner of my eye. There, just across the property line, thirty prairie chickens are flying in. Even though a row of windbreak cedars lie between us, I instinctively hit the deck. “West! West!” I hear Jeremy call. All of the hunters nearby hold their breath, but the birds land in short grass not fifty yards across the property line.

There’s nothing we can do but wait. I try to guess where the birds will fly next, eyeing the swale we passed on. We are committed to our current position though- if we try to move anywhere, the birds will flush off in the wrong direction.

Without warning, the whole flock goes, cutting into the cut hay field. It is excruciating to watch them sail over the fence and wing directly up the swale. We are 75 yards away from being in a perfect position. None of the other hunters have a better spot, and I am impressed at their restraint. No one tries to skyblast the birds, and they land out of reach in the field’s barren center.

With less than twenty minutes of legal shooting light remaining, the action turns on. Chickens soar into the field from all directions in flocks of tens and twenties. Luck is in their favor, with most drawing only a couple shots from the nearest hunter.

Just when I think my opportunities are gone, I hear a call of “East! East!” Sure enough, a healthy flock is flying right down the fenceline toward us. They’re rather high, powerful wingbeats sustaining them on a long flight toward their nightly roost. Dan and I sprint down the fenceline to get into a better position.

The birds see us at the last minute and bank away, but not before Dan and I unload on the nearest chicken. Six shots from two 12 gauges, but at least one pellet flies true. The heart-shot bird flutters high, then loses speed.

A last hunter on the corner of the field fires at the failing bird, and it drops with a thud. The sun sets in orange splendor behind him as he holds the prairie queen high.

Just as suddenly as the action began, it is over. We see the lights of Billy’s side-by-side bounce to and fro as he shuttles the young and old hunters back to their vehicles. Jeremy, Dan, and I walk back to the truck. We all know what just happened, but we still can’t help but replay the experience, building stories around this brief but powerful encounter with the regal native grouse of the central plains.

When we arrive back at the trucks, headlights shine on tired but satisfied faces. Five birds are laid out with reverence at the side of the road. Both kids and the grown-ups can’t resist stroking the cream and chocolate bars and twirling the pinnae feathers on the necks of a few trophy males.

It’s only a fraction of a bird per hunter, but ask any of these folks if it was worth a dark-to-dark day, and I’d get a hearty “Yes!” “Sometimes we get a lot, sometimes a few," says Billy. “In the 1980’s and 1990’s, we occasionally brought home a hundred birds. We’ve gone out many times and not harvested any.”

The Jackson family is content to only hunt prairie chickens once a year. Lots of work goes into planning the event, including months of scouting the best fields to target. Even though they could hunt these fields every day through the late season or walk up chickens behind Jeremy's bird dogs, they choose not to.

Some years, more hunters are in just the right spot, some years they aren’t. The tenuous fortune of a pass-shoot prairie chicken hunt holds an undeniable romance. The precepts of sustainable harvest and fair chase are baked in. The goal isn’t really to shoot a lot of birds anyway. Reuniting with friends and family to appreciate the central prairie landscape and the birds that inhabit it – these are the reasons we are here.

The future of prairie chicken hunting in Kansas isn't guaranteed, with slowly declining bird numbers. Jeremy explains why. “It’s the habitat. This is historic ranching country, but unfortunately some of the prairie is now owned by large corporations.”

Jeff Prendergrast agrees. “Grassland loss is the number one threat to prairie chickens. This loss can be from the direct conversion of grassland to cropland (which is still occurring at an alarming rate), the loss of grasslands to trees through succession, or loss of grassland to energy development.”

It is increasingly common for landowners to overgraze their pastures, stocking more cows longer. Livestock producers also burn the rangeland to improve forage, but fire is a double-edged sword. In some areas, spring burns are too frequent and extensive, eliminating crucial nesting habitat. In other areas, prescribed burns aren’t used at all and trees take over, including invasive red cedar.

As quality habitat becomes more fragmented, prairie chicken populations are less equipped to absorb the other factors that impact their numbers – things like predation, weather fluctuations, and disease.

Because the vast majority of Kansas is private land, keeping chickens on the landscape means supporting landowners who want to maintain a healthy prairie. Spencer Heise is a Farm Bill Biologist with Pheasants Forever/Quail Forever (PF/QF). He works with Flint Hills landowners to “Reduce woody encroachment, cut and remove trees, and plant broken ground back to native range.”

While funding on-the-ground habitat work is critical, so is education. Spencer says The Kansas Great Plains Grassland Initiative aims to teach Kansans what constitutes a healthy prairie, and help landowners make it a reality.

Billy and Jeremy Jackson are dedicated to keeping their family chicken hunt alive. Even though bird numbers are declining, KDWP is confident that they can maintain a sustainable harvest. With limited public hunting access, some areas in the Flint Hills and Smoky Hills are seeing increasing hunting pressure, but the bulk of the prairie chicken range sees few if any hunters.

The annual chicken hunt is important to the Jackson family, but such hunting traditions have more than esoteric value. Jeff Prendergrast says, “It may seem counterintuitive, but hunting chickens helps create a connection and appreciation for this species that would otherwise not exist. When we lose the opportunity to pursue a species, we often lose the biggest advocacy group for them.”

The hunters pack up to drive back to Wichita and Kansas City. As the party disperses into the night, Jeremy’s young cousin Reece cradles his first prairie chicken. He’s been attending the event since he could walk, but tonight he holds his own bird, taken with a single shot .410. He will carry it home with a stalwart love for these beautiful birds, the Kansas prairie that they inhabit, and his family’s hunting tradition.

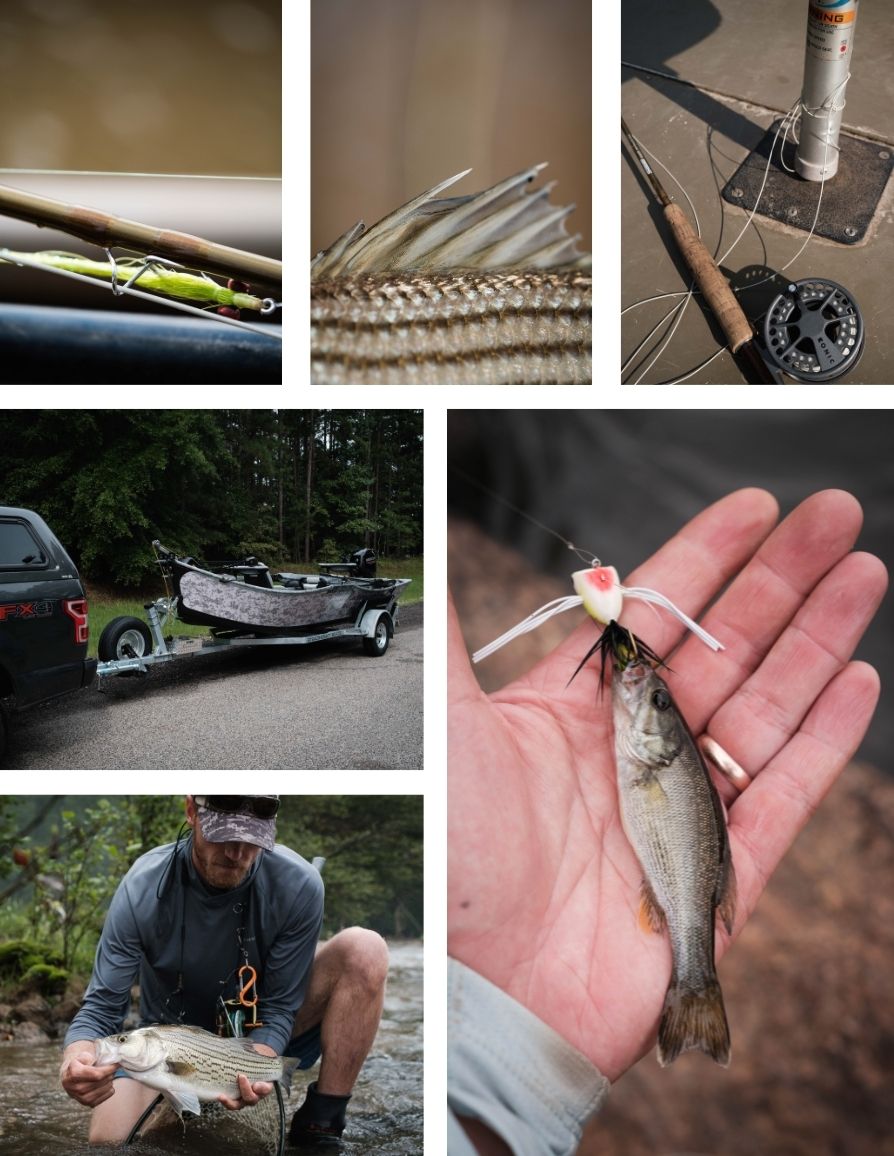

Photo Essay

Warm Water on the Fly

Words and Photos by Sammy Chang

Our earliest fishing memories are often rooted in small ponds for largemouth bass, bluegill or catfish. In these places, and these fish, we learned the “tug is the drug” and found an immutable joy for our angling souls.

Then, at some point, we found cold water and trout, and our pursuit of those warm-water species played second fiddle to their cold-water brethren.

But with the cast of a popper on a glass-slick pond in early summer, a plop, plop, and SPLOOSH can unlock those childhood core memories faster than a released bluegill darts back to its hide. And we remember again, that the tug is the drug, no matter what species. An endless supply of fly-fishing opportunities often lies closer than a stone's throw away. Micro-ecosystems you were unaware of, violent takes on top water; all awaken the child in you.

A friend sent me a picture recently. He is retired, and has the world of fishing at his fingertips. But I’ve never seen as big a grin as when he recently landed his first catfish on the fly. It was akin to the grin my nine-year old daughter sported when she casted, set, and landed her first bluegill on a small rubber-leg popper.

Unlock those core memories and chase fish wherever they are.

Warm-water fly fishing opportunities are often closer and more accessible, whether on foot or by watercraft. Simplicity at it’s best; all you need is a handful of flies and a simple leader. And sometimes, good line management.

A vast array of species await, each with their own splendid ecosystem and features.

From small vibrant sunfish to river-running stripers, warm-water offers an experience worth repeating.

Hatches

Gear Spotlight & Giveaway:

This month’s giveaway includes three total packs - 1) Hydrate & Recover ($49.95 value), 2) Rescue Hydration ($19.95 value), 3) Energy & Focus ($49.95 value); a Wilderness Athlete Nalgene bottle ($14.95, not pictured) and Wilderness Athlete hat ($24.95, not pictured) as well as a $50.00 off coupon for future purchases. Total value $209.75. Bottle in images is for demonstration and is not included in the giveaway.

Giveaway ends at 11:59 pm EST on 9/30/2025. One winner will be selected at random and contacted by email. Winner has 48 hours to respond or another winner will be selected.

Congratulations to Alan Taylor, winner of our Smith Optics Hookset giveaways from Issue 001, and Daniel McKenzie, winner of the Stio CFS Board Pants from Issue 002.

I’ve spent a lifetime dealing with leg cramps. From my days playing soccer to my yearly backcountry trips, around the three-mile mark, I feel them coming. No amount of training seems to counteract the effects of a loaded pack on my legs. I try to shift the pack weight, walk like a duck—anything to avoid the cramps, which only make other muscles cramp.

This year, I decided to try hydration packets (yes, I am late to the game; I’ve always been a water-only hydrater) and went with a few offerings from Wilderness Athlete. They are outdoorsmen first and foremost and have spent the better part of two decades in the performance nutrition and hydration industry.

Figuring my cramps were impending, I opted to pre-hydrate with their Hydrate & Recover formula. I tried Berry Blast. Unlike memories conjured up from childhood, Berry Blast was not a sugar bomb, but had a pleasant and refreshing, non-chemical taste and left no foul aftertaste. I do feel like it made the in-hike much more pleasant, with no hike-pausing cramps.

The real test came after several days spent wading backcountry streams and the long hike out on fatigued legs. Halfway into the hike, I felt my quadriceps heading to cramp-land. I tried to reposition and change my posture, only to feel my calves start tightening. At this point, I opted to down a packet of their Rescue Hydration powder. I gave it 10 minutes and felt like a new man and was able to complete the hike out without hike-pausing cramps, as I’ve had in the past.

I like the fact that I am buying products that are 100% sourced, tested, and produced on American soil and that I am supporting a family-owned and operated business. I can recommend their products wholeheartedly.

Partners in Conservation

We strongly believe in paying it forward; we owe it to the species we pursue, the land we are called to steward, and future generations of sportsmen and women to come. We are proud to support these organizations.

If you enjoyed this issue, we would greatly appreciate if you would spread the word. Forward it to a friend, a coworker, a son, a daughter, a family member. We rely on our subscribers and the brands that support us to keep the quality content flowing and free. Even sending it to one friend goes a long way. And remember, you can earn free stuff now for your referrals. Thanks you in advance!